Small Business May Play a Not-So-Small Part in Restarting Hawaii's Economy

This is part of a series of posts highlighting results from the Hawaii COVID Contact Tracking Survey conducted by the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC) and the Pacific Urban Resilience Lab (PURL) at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The Hawaii Data Collaborative has partnered with this group to share regular analyses and updates from this survey in the coming weeks. If you have not done so already, we encourage you to participate in the survey here.

Hawaii has over 700,000 people in its civilian labor force. The large majority work for small businesses.[1] In 2017, there were approximately 540,000 people who worked for small businesses or about 80% of all employed individuals.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of workers by industry and establishment type (left panel). The two largest industries in the state by number of workers—accommodation and food services and retail trade—have been among the hardest hit by the economic impacts of COVID-19. The effect on those two industries was overwhelmingly felt by small businesses (middle panel), which contribute billions of dollars to Hawaii’s economy each year (right panel).

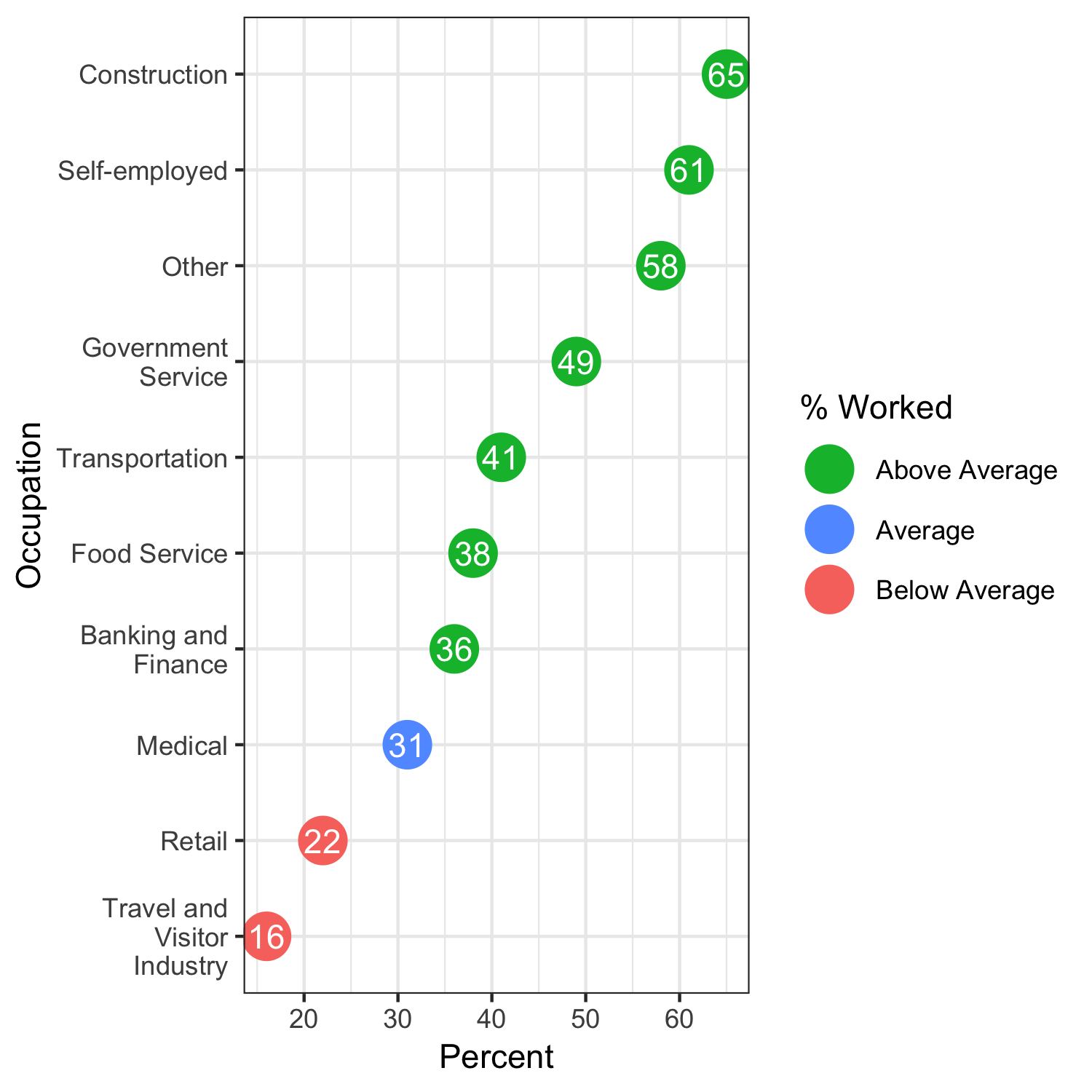

Among survey respondents who reported an occupation in retail or the travel and visitor industry, 22% and 16% (respectively) reported working in the past 5 days—9 and 15 percentage points lower than the average of all respondents (31%, see Figure 2). Again, these numbers reflect the severity of the impact the pandemic has had on these two industries in Hawaii.

Workers in other industries may be faring better during this pandemic. Construction workers, for example, make up a significant proportion of the workforce, many of whom have retained relatively steady work. In our survey, 65% of respondents in construction said they went to work in the past 5 days—the highest percentage among all survey respondents by occupation (Figure 2).

Another intriguing statistic is the fact that only 31% of healthcare workers said they went to work in the past 5 days. Given the pandemic, one would have expected that number to be higher. But a closer look reveals a majority of healthcare workers are employed by small businesses—entities that are often engaged in elective surgeries and procedures, and may not be directly involved in care related to the pandemic or connected to large hospitals. While social distancing may be less of a problem between their staff members, does the type of service they provide put greater limits on their ability to restart their businesses?

In the local retail industry, most workers are also employed by small businesses. Is finding ways to maintain social distancing between customer and staff more of an issue than maintaining distances between staff members themselves in those businesses?

These are important statistics and issues to keep in mind as the state begins to look beyond the current pandemic and search for strategies on how to restart the economy. Low-contact small businesses could be prime candidates to help restart the economy with a minimum of risk. Could these work populations provide us with a methodical way to expand local economic activities beyond those deemed essential? Can we safely expand those essential businesses already operating?

Clearly, the first step would be to determine the type of companies that would participate in a phase-in and then establish safety guidelines for those businesses. More importantly, the data highlight a dilemma we all face in this pandemic: Too often, we have been forced to make what seems like either-or choices – take care of a parent, or risk exposing ourselves and them to the virus; go to work, or risk exposing our entire family; close businesses, or risk spreading the virus to others. If anything, the pandemic has heightened our awareness that financial health is as important as any factor that affects our overall wellbeing.

To be free of the virus but to be without a job, income, food or shelter is not a formula for long-term good health. Instead, good health and life is a balancing act. And so is the decision to restart the economy here in Hawaii. It may not be a question of whether we do it or not, but when and how we do it. Addressing small business issues and understanding how they operate may be the key to how well we do that.

Related Posts in this Series

Insights From the Hawaii COVID Contact Tracking Survey

The Good, The Bad, and Social Distancing in Hawaii

Ongoing and Comprehensive Information Key to Reopening Hawaii

Our Kupuna: Understanding Their Risks

Contact Tracing versus Contact Tracking

How Vulnerable is Hawaii in the Face of a Coronavirus Pandemic?

Underlying Health Conditions and How They Impact Our Vulnerability in Hawaii

Family Ties: Are Hawaii’s Multigenerational Families More at Risk?