Contact Tracing versus Contact Tracking

This is part of a series of posts highlighting results from the Hawaii COVID Contact Tracking Survey conducted by the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC) and the Pacific Urban Resilience Lab (PURL) at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The Hawaii Data Collaborative has partnered with this group to share regular analyses and updates from this survey in the coming weeks. If you have not done so already, we encourage you to participate in the survey here.

Among the many new terms that have crept into our daily language, contact tracing has become one of the most frequently heard in connection with COVID-19. Contact tracing is a traditional public health strategy that has been used to fight the spread of everything from the common flu to the AIDS virus. We often hear public health officials talk about the need to employ contract tracing to not only get the current pandemic under control but to keep the virus from flaring up once we start to reopen cities and states.

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contact tracing is the method used to identify the personal and incidental contacts of those who have tested positive for a communicable disease and to notify those individuals of their potential exposure. The process also attempts to identify the contacts of the secondary group (and beyond if resources are available) to help ensure that a comprehensive system of targeted, sustainable and effective quarantine can be implemented to prevent additional transmission.

The strategy was one of the primary tools used to stop the spread of the Ebola virus in Africa in the mid-1970s and AIDS in the U.S. It continues to be used today to prevent regional outbreaks of communicable diseases from becoming widespread. However, it is also generally acknowledged that the strategy, whether local or nationwide, is extremely labor intensive and would require an army of contact tracers in this current pandemic.

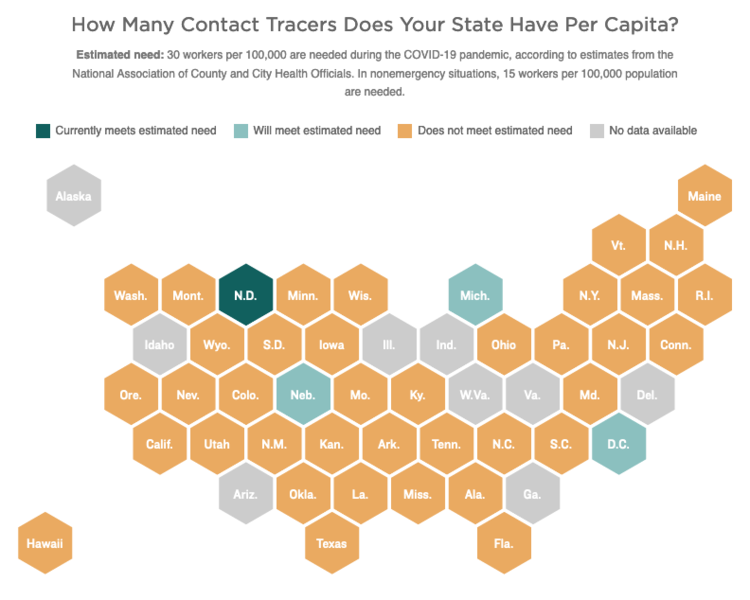

For example, it takes about 30 contact tracing personnel with the various skillsets for every 100,000 in the population. These would include both trained professionals and volunteers—disease investigation specialists, public health nurses, community health workers, public health social workers, and epidemiologists.

Under this formula, Hawaii would need about 420 such individuals for our resident population—not counting visitors. Varying reports from the state estimates there are between 30 to 80 individuals currently tracing contacts of those who have tested positive for COVID-19 in Hawaii. Others estimate the need could be far greater than that.

In addition, the strategy relies almost exclusively on testing to begin the process and is time consuming in its reliance on one-on-one interviews. However, technology—including smart phones, tracking devices and programs, social media platforms, case management tools, and data collection programs—is also changing the face of contact tracing and facilitating the process even as we speak.

We call our type of online survey contact tracking. The survey relies on technology and social media to provide insights into trends, tendencies and probabilities for how, when, where and why the virus might spread throughout the islands. While not as specific in nature as contact tracing, our surveys attempt to get to similar kinds of information from a statistical approach.

Moreover, as an online tool, the delivery time is nearly immediate without dependence on testing to initiate the process. Online surveys are part of a new breed of tools in the science of epidemiology that tap into the popularity of social media, the ubiquitous presence of the personal computer and the Internet, and the incredible leverage that computer science has given to statistical analysis.

Just days after posting our survey, we started receiving responses and within a week we were analyzing data from about 11,000 respondents. A second survey produced an additional 11,000 new or follow-up responses—that as the state began initiating contact tracing for just under 600 of those who tested positive for the virus.

Granted, testing and contact tracing provide a more direct approach to securing specific information to help curtail the pandemic. But in the face of limited testing and contact tracing, we believe our online survey is providing helpful supplemental information to Hawaii’s public health professionals and decision makers at a critical time in this pandemic.

The bottom line is not that one method is better than the other. Rather, together, testing, contact tracing and timely online surveys (contact tracking) can provide a more complete picture of the pandemic and the factors that inflame, direct, and curb its spread. Each plays a key role in fighting the virus and stopping the pandemic. Contact tracing is central to any strategy in getting us back to any kind of normalcy. Online surveys, like ours, can be used to not only understand the virus and its spread, but also make contact tracing much more efficient.

Moreover, testing and contact tracing, at the levels required, may be just as far down the road as a safe and effective vaccine is. And that—without alternative means of gaining useful and timely information—is a scary thought.

Related Posts in this Series

Insights From the Hawaii COVID Contact Tracking Survey

The Good, The Bad, and Social Distancing in Hawaii

Ongoing and Comprehensive Information Key to Reopening Hawaii

Our Kupuna: Understanding Their Risks

How Vulnerable is Hawaii in the Face of a Coronavirus Pandemic?

Small Business May Play a Not-So-Small Part in Restarting Hawaii’s Economy

Underlying Health Conditions and How They Impact Our Vulnerability in Hawaii

Family Ties: Are Hawaii's Multigenerational Households More At Risk?